Can we reimagine AI?

This story is one of many that reveal the extraordinary legacy of Boundless: the Campaign for the University of Toronto, which ended on December 31, 2018. Read more inspiring stories of impact and discover why more than 100,000 people came together to make the Boundless campaign an historic success.

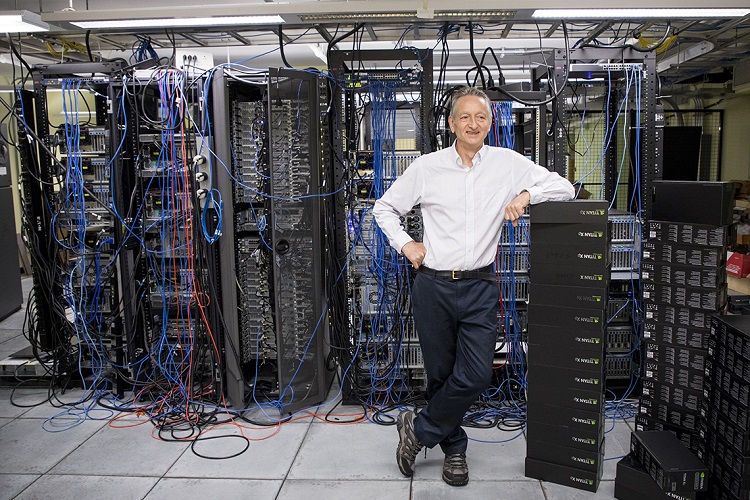

University Professor Emeritus Geoffrey Hinton, a pioneer of the AI field, keeps making breakthroughs. The latest is a novel way to teach computers to identify something they've never seen before.

Geoffrey Hinton may be the “godfather” of deep learning, a suddenly hot field of artificial intelligence, or AI – but that doesn’t mean he’s resting on his algorithms.

Hinton, a University Professor Emeritus at the University of Toronto, has published his thinking on “capsule networks” – a concept that promises to improve the way machines understand the world through images or video. The technology has applications that range from building better self-driving cars to making medical diagnoses.

“This is a much more robust way to detect objects than what we have at present,” says Hinton, who is also a fellow at Google’s AI research arm.

“If you’ve been in the field for a long time like I have, you know that the neural nets that we use now – there’s nothing special about them. We just sort of made them up.”

Keeping Canada at AI’s cutting edge

Hinton’s approach, detailed in a story in Wired magazine, relies on these “capsule networks.” Here’s how it works: At present, deep learning algorithms must be trained on millions of images before they can reliably distinguish a picture of, say, a cat from something else. In part, that’s because the software isn’t very good at applying what it’s already learned to brand new situations – for example, recognizing a cat that’s being viewed from a slightly different angle. Capsule networks, by contrast, can help track the relationship between various parts of an object – in the case of a cat, one example might be the relative distance between its nose and mouth.

At Google’s Go North conference, held at Toronto’s Evergreen Brick Works, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said it is important for Canada to continue to play a key role in shaping the development of AI technologies because “if we’re helping drive it, we will draw benefits from it and minimize the challenges and disruptions as we bring people along.”

With his new research, there’s little doubt Hinton is doing his part to move the AI ball forward – even if it draws on ideas he’s been contemplating for the past 40 years.

In published results, Hinton’s capsule networks matched the accuracy of the best previous techniques when it comes to recognizing hand-written digits, according to Wired. A second test, one that challenges software to recognize objects like toys from different angles, cut the previous error rate in half.

“What we showed is early days,” Hinton cautioned attendees at Go North. “It works quite impressively on small datasets. But until it works on large datasets, you shouldn’t believe it.”

Even so, other researchers are lauding Hinton’s efforts.

“It’s too early to tell how far this particular architecture will go,” Gary Marcus, a professor of psychology at New York University, told Wired. “But it’s great to see Hinton out of the rut that the field has seemed fixated on.”