‘Canada’s sweetheart’ Anne Murray donates archives to U of T

Featured Image Caption

Featured Image Caption

Music legend Anne Murray has donated 40 years of documents, recordings, contracts and memorabilia to U of T Libraries, offering a unique window into the Canadian popular music industry.

Posted on November 24, 2017

University of Toronto will be home to the archives of Canada’s music legend Anne Murray.

The first Canadian female solo singer to reach No. 1 on the U.S. charts, whose albums have sold over 55 million copies worldwide, Murray has donated her extensive archives to U of T Libraries.

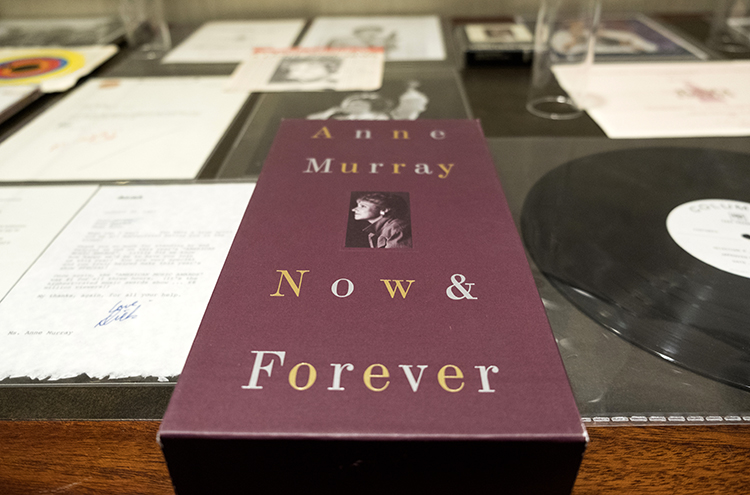

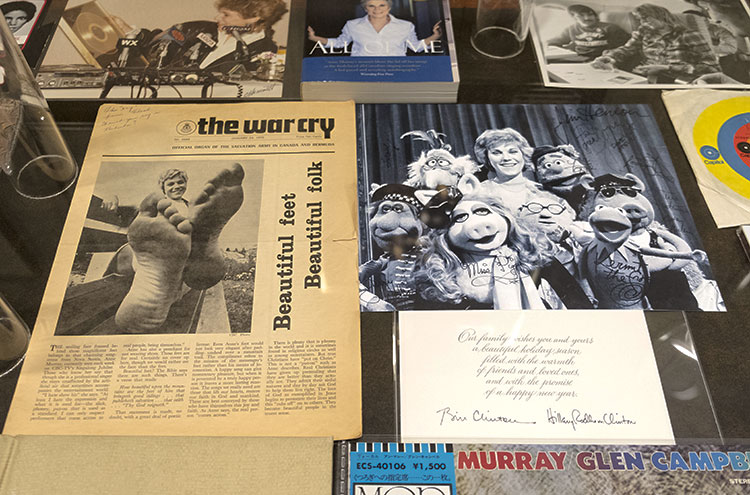

The collection includes more than 70 boxes, containing 188 LP albums from around the world, nearly 900 photographs, 253 audiotapes and cassettes going back to the time Murray was 18, videotapes of her television appearances, yearly scrapbooks of clippings, fan mail from the likes of ABC anchor Peter Jennings and a thank-you note from TV host Dick Clark, to name a few.

The complete record of a stellar Canadian career

“Every television show I ever did, every tape I ever made, people will have access to this,” Murray said in an interview with U of T News. “A lot of the places I played – Carnegie Hall, Radio City Music Hall, Royal Albert Hall in London, the Palladium in London – it was at the time, monumental for me. Everything’s there.”

U of T Libraries announced the donation of Murray’s archives at an event at Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. Murray’s 40-year career saw her win four Grammy Awards, 24 Juno Awards, three American Music Awards and three CMA Awards.

“She embodies the Canadian popular music industry,” said Brock Silversides, director of U of T Libraries’ Media Commons, which houses an audiovisual library and media archives at Robarts Library. “She’s been so successful within Canada and internationally. She’s really identified with Canada, even one of her songs Snowbird, that’s so Canada.

“Just with her voice alone, she’s become enormously successful and has affected a lot of people. At the risk of sounding like a cliché, Anne’s music has been the soundtrack to many people’s lives.”

Deciding to save unique historical materials

A note from Dick Clark (left), photographs, LPs and videos are among the more than 70 boxes of material in the Anne Murray archives at U of T Libraries’ Media Commons. Photo by Laura Pedersen.

Dressed in a blue leather jacket, Murray, 72, was her down-to-earth self at the announcement, recalling why she decided to donate the archives. At the time, she was moving from her Toronto area home of 38 years to a condo, she said, and a squash court in the house was doubling as a storage room.

“It was wall to wall shelves with 40 years of memorabilia,” Murray said. “I had no idea who, if anybody, would want that.”

Well, U of T did. The university’s extensive library system houses the archives of well-known Canadians like Leonard Cohen and U of T alumna Margaret Atwood, whose collections reside at the Thomas Fisher Library.

In this case, a friend of Murray’s, music journalist Marty Melhuish, had also donated his material to U of T. He put her in touch with Silversides. Murray recalled her initial phone conversation with the head of Media Commons.

“I said to him, ‘If you don’t want this stuff, I’m going to light a match to it,’” Murray said. “I didn’t see his face. But there was almost an audible gasp.”

Demo tracks, unreleased recordings, contracts: “A magical resource”

The collection includes photographs, and magazine and newspaper clippings. The photo to the right is from The Muppet Show in 1980. The collection also includes a holiday card from Bill and Hillary Clinton. Photo by Laura Pedersen.

The collection includes demo tracks and unreleased recordings, and every contract for every record, TV and live performance Murray did until her retirement in 2008. There’s a framed gold record from Capitol Records, from sales of Let’s Keep It That Way, in Australia in 1982. U of T librarians hope the archives will offer a window into the music industry and how it worked.

“For somebody who’s wanting to reconstruct her career, it’s all there,” Silversides said. “One of the strong points of the collection is it’s so comprehensive. It covers her entire career and almost any way she has been documented. You would gain quite an insight into how she handled her career, how she dealt with people.”

U of T Provost Cheryl Regehr spoke at the event, remembering family dinners in the living room watching Anne Murray’s Christmas special on TV.

“These kinds of archives really give us a critical glance into the working mind, and allow us to appreciate true genius as it evolves when we have the opportunity to see work in progress and the finished work. For our students in history, music, Canadian studies, popular culture, this is really a magical resource that’s here for us.”

Reflecting on hard work and extraordinary success

Album covers in the collection are from around the world, including Japan and Germany. Photo by Noreen Ahmed-Ullah.

Murray herself said she hopes members of the public who have access to the digitized archives will see how hard she worked.

“I was on the road so much. You can see by the itineraries that are there. It’s incredible. I look at it, and wonder how I did it. And remember, I had a young family too,” she said. “It was my job, and when it’s your job, you do it, whatever it entails.”

But she said the work was never boring. “You go from doing television shows, to in studio doing albums, to live shows. There were so many facets to the business. But boy, it sure kept you going.”

Looking back now, Murray said maybe the key to her success was her voice. “It was a combination of the sound of my voice – when you hear my voice on radio, there’s no mistaking it – I haven’t heard anyone else who sounds like that ever, except my brothers and my kids.

“It was a very unique sounding voice, and I was good too. But maybe I was in the right place at the right time. I just don’t know. I just feel fortunate that all of those things happened when they did.”

Living in the public eye – was it worth it?

Scrapbooks include clippings of every article written about Murray through her career. Photo by Noreen Ahmed-Ullah.

One thing the public won’t see in the archives is information about her personal life. Murray, who decided to do a tell-all memoir in her 2009 autobiography, All of Me, said she wanted this collection to be about her career.

“I’m very personal,” she said. “I keep close things to the chest, but the career was something else. I share that with everybody else.

“As a matter of fact, my family often wishes I hadn’t done it. My son once said when they asked him if he was going to get into show business, he said, ‘Why would I do something that took my mother from me?’ And that’s true. Why would he? It was hard on the kids.”

Will she ever come out of retirement to sing again? Murray said not likely.

“No. Once I made up my mind, that was it. Forty years is long enough to do anything, and it was hard work. A lot of sacrifices. A lot of compromises. Even as I look back, I say, ‘Was it worth it?’ I don’t know. It’s what I knew how to do. It’s what I was good at. And how do you turn away from that?”

By Noreen Ahmed-Ullah