How a travel grant built a more effective architect

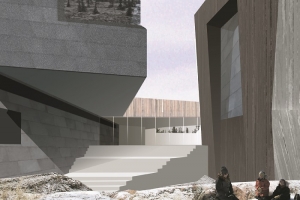

Featured Image Caption

Featured Image Caption

A donor-supported travel program helped architecture students learn, hands-on, about the importance of collaboration in design.

Posted on September 26, 2017

Taking learning outside the classroom can lift an education from good to great. For Kearon Roy Taylor, a student in the Master of Architecture program at the University of Toronto, a trip to Yellowknife with professor Mason White provided first-hand insight into the social impact of architectural designs, and gave him an experience of real-life collaboration that is invaluable.

“Part of the training of an architect is to learn to be a good listener, a keen observer,” says White, a professor at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design. “You have to be a kind of detective when it comes to understanding both the needs of people, and the opportunities of a place and a context.”

Designing a community-centred wellness centre

In the fall of 2016, White taught a course offering Taylor and 14 classmates a unique opportunity: the chance to create design concepts for an Indigenous wellness centre in Yellowknife. A facility like this—culturally sensitive, independently operated—would help fulfill the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The Dene, Inuit and Métis communities in Yellowknife envision offering traditional healthy foods, medicines and spiritual guidance to patients who choose to pursue traditional healing and preventive care.

The project incorporated a number of architectural challenges, says White, who studies how design relates to the environment and people, and is co-founder of the award-winning studio Lateral Office. The students’ proposals had to address the unique cultural needs of the people that would use the centre, but also be sustainable, practical for a far northern climate and affordable.

“Always working in the city, I think students get a bit complacent,” says White. “To disrupt their familiar territory is to get them to discover some new things. So this being such a unique place, and such a unique people, it was a nice opportunity.”

The design concept created by Kearon Roy Taylor and fellow student Genevieve Simms accommodates outdoor and indoor spaces.

Collaborating with elders and health experts

Travelling to Yellowknife thanks to a donor-funded grant, the group met with Dene elders and viewed the project site. When they returned to U of T, they consulted further with First Nations House and the Institute for Circumpolar Health Research, then brought Dene Elder Francois Paulette to U of T for further conversations.

The students learned that designing a culturally sensitive building isn’t about superficial aspects. “Unfortunately, heavy-handed symbolism can be common,” says White, “such as designing an Inuit building in the shape of an iglu. It would be better to be inspired by the iglu as a principle of efficiency.

“With this project, we were trying to acknowledge the diversity of spaces required in a health centre, and so we were asked to provide spaces in which multi-generational exchanges could occur, spaces in which rites of passage for certain ages could be acknowledged or celebrated. And to acknowledge the role that food plays in good health and cultural reinforcement.”

The students also tried to incorporate local building materials, and be sensitive to specific local geography—such the length of days in the land of the midnight sun. “Access to light can be precious in some seasons, and in other seasons you really need to protect yourself from the sun,” says White. “The students were really ingenious about the roof and windows.”

A series of seven connected spaces and creative window treatments bring a multi-use space alive. Design by Kearon Roy Taylor and Genevieve Simms.

Donors directly help students transform communities

While student designs can’t be built in reality (architectural projects require professional registration), the U of T proposals gave insight to both the Yellowknife community and the budding architects. “I was able to gain a deeper understanding of the centre’s cultural context,” says Taylor, who is on track to graduate in 2018. “This opportunity—to meet with the people who will benefit from the centre and collaborate with someone whose passion and expertise I respect so much—has been life-changing.”

Gifts to U of T’s Annual Funds are key to transformative student experiences like this one. The University can direct such support where it is urgently needed, making the impact of your gift immediately apparent. As well as offering opportunities to get hands-on in the field, annual fund donors are supporting everything from scholarships and bursaries to original research projects to student services and programming.

And in a world where an architect can be a powerful advocate for under-represented people, travel initiatives are the kind of education that can grow global citizens—people who transform communities. A charitable nonprofit, the Arctic Indigenous Wellness Foundation, has now been established in Yellowknife to make the wellness centre a reality.